I went to Ottawa hoping to be an Indigenous woman in the Cabinet and contribute teachings and learnings from the Indigenous experience in this country to making good decisions and setting better policy. I ended up being treated as the Indian in the Cabinet. Became the Indian out of the Cabinet and finally the Indian out of the party. An unusual tale? Perhaps not so much.

When I set out to write this book, I was reminded by Kory that she had recorded over eight hours of our grandmother speaking about our peoples’ ways and her life. As I said earlier, Kory recorded these tapes in 1990, when our grandmother was nearing the end of her life. Sometimes my auntie Annie and auntie Lilly and Fred are in the conversations as well. My granny, her sister, and her cousin move between English and Kwak’wala. All of them were recorded at my granny’s kitchen table, by her window that looked out over the cherry tree to the right of the grass and, off to the left, the second green of the Comox Golf Club.

I had not listened to these cassettes before writing this book. When I played the first one on an old cassette machine and heard my grandmother’s voice my eyes flooded with tears—the kind of tears that come when memories are so vivid and intimate it feels like they overtake every aspect of your being. I could feel everything of her. Her words dripped with the learning of thousands of years of oral history and the wisdom gained through a life fully lived.

On the recordings, she reflects on the disruptions our system of governance has experienced and laments the contemporary reality of our people, on which outside forces have had large impacts. She asks whether we, as a people, still really know who we are. When she lovingly shares stories about my dad, she talks of how she may have named him wrong. “Your father is too voluble to be a Hamatsa,” she says. As part of the Hamatsa society—as a Chief—you are not supposed to raise your voice; you are supposed to be observing, taking everything in, and maintaining balance. But in this contemporary world, because of how things have changed, Dad had to lead in the outside world, and he needed to do what he was doing because of those changes.

She also talks on the recordings about the Potlatch, about how our people maintained governing through the Potlatch even after it was outlawed by Canada through the Indian Act. She talks about how our people would disguise the Potlatch from the Indian agents that would travel to Kingcome by boat. They had lookouts along the way, on the shore. And when the signal came that the Indian agent was close by, those assembled would start singing “Onward Christian Soldier” to trick the agent into thinking they were just being “good little Indians.” When the political organization of the Native Brotherhood was in its early days, they followed a practice of singing that same hymn at the beginning of every meeting.

In the shadows, hidden from view, resilience, survival, and the work of advancing justice carried on. Our governance systems were nurtured and maintained by my recent ancestors and their generation at significant risk and cost. The struggles undertaken by them allowed our ways to survive and to come out of the shadows, and to be revitalized and rejuvenated. They knew what was needed for us, as Indigenous peoples, to once again govern ourselves in ways that respect our legal traditions and, in so doing, support the cultural, social, economic, and spiritual well-being of our peoples. This history of survival is a part of being who we are, and who we will always be.

I think of the sacrifice my grandmother and so many others had to make to keep something known and alive—to make sure it could thrive again. And I realize that throughout my journey to Ottawa I was looking at her in the mirror, and she was guiding me each step of the way. She had already shown the way, as our Elders do. She had passed on the knowledge and responsibility, and we each have a role to play in our time. While my grandmother and the “old people” had to maintain ways of governing without being seen, I, like my father and other leaders, had to do my part with everyone seeing. While my grandmother and my ancestors used the shadows to keep something strong, I had to endure the glare of the public eye to raise an alarm about what was hidden from view.

Isn’t that the way of change—the unseen becoming seen? A lot that was unseen within me I now see because of my journey to Ottawa and back. I hope some light was also shone on some of the challenges we face, and where we still must go as a country. I believe it has, and for that I am grateful.”

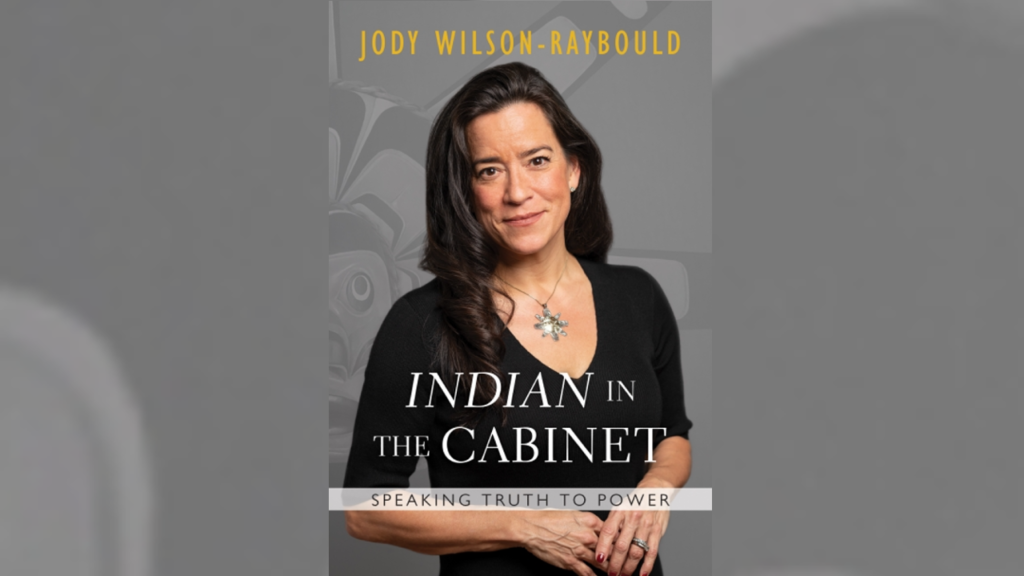

Jody Wilson-Raybould is the former Attorney-General of Canada

Jody Wilson-Raybould

Jody Wilson-Raybould